QWERTY

QWERTY (/ˈkwɜːrti/ KWUR-tee) is a keyboard layout for Latin-script alphabets. The name comes from the order of the first six keys on the top letter row of the keyboard: QWERTY. The QWERTY design is based on a layout included in the Sholes and Glidden typewriter sold via E. Remington and Sons from 1874. QWERTY became popular with the success of the Remington No. 2 of 1878 and remains in ubiquitous use.

History

The QWERTY layout was devised and created in the early 1870s by Christopher Latham Sholes, a newspaper editor and printer who lived in Kenosha, Wisconsin. In October 1867, Sholes filed a patent application for his early writing machine he developed with the assistance of his friends Carlos Glidden and Samuel W. Soulé.[1]

The first model constructed by Sholes used a piano-like keyboard with two rows of characters arranged alphabetically as shown below:[1]

- 3 5 7 9 N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z 2 4 6 8 . A B C D E F G H I J K L M

Sholes struggled for the next five years to perfect his invention, making many trial-and-error rearrangements of the original machine's alphabetical key arrangement. The study of bigram (letter-pair) frequency by educator Amos Densmore, brother of the financial backer James Densmore, is believed to have influenced the array of letters, although this contribution has been called into question.[2]: 170 Others suggest instead that the letter groupings evolved from telegraph operators' feedback.[2]: 163

In November 1868 he changed the arrangement of the latter half of the alphabet, N to Z, right-to-left.[3]: 12–20 In April 1870 he arrived at a four-row, upper case keyboard approaching the modern QWERTY standard, moving six vowel letters, A, E, I, O, U, and Y, to the upper row as follows:[3]: 24–25

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 - A E I . ? Y U O , B C D F G H J K L M Z X W V T S R Q P N

In 1873 Sholes's backer, James Densmore, successfully sold the manufacturing rights for the Sholes & Glidden Type-Writer to E. Remington and Sons. The keyboard layout was finalized within a few months by Remington's mechanics and was ultimately presented:[2]: 161–174

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 - , Q W E . T Y I U O P Z S D F G H J K L M A X & C V B N ? ; R

After they purchased the device, Remington made several adjustments, creating a keyboard with essentially the modern QWERTY layout. These adjustments included placing the "R" key in the place previously allotted to the period key. Apocryphal claims that this change was made to let salesmen impress customers by pecking out the brand name "TYPE WRITER QUOTE" from one keyboard row is not formally substantiated.[2] Vestiges of the original alphabetical layout remained in the "home row" sequence DFGHJKL.[4]

The modern ANSI layout is:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 - = Q W E R T Y U I O P [ ] \ A S D F G H J K L ; ' Z X C V B N M , . /

The QWERTY layout became popular with the success of the Remington No. 2 of 1878, the first typewriter to include both upper and lower case letters, using a ⇧ Shift key.

One popular but possibly apocryphal[2]: 162 explanation for the QWERTY arrangement is that it was designed to reduce the likelihood of internal clashing of typebars by placing commonly used combinations of letters farther from each other inside the machine.[5]

Differences from modern layout

Substituting characters

The QWERTY layout depicted in Sholes's 1878 patent is slightly different from the modern layout, most notably in the absence of the numerals 0 and 1, with each of the remaining numerals shifted one position to the left of their modern counterparts. The letter M is located at the end of the third row to the right of the letter L rather than on the fourth row to the right of the N, the letters X and C are reversed, and most punctuation marks are in different positions or are missing entirely.[6] 0 and 1 were omitted to simplify the design and reduce the manufacturing and maintenance costs; they were chosen specifically because they were "redundant" and could be recreated using other keys. Typists who learned on these machines learned the habit of using the uppercase letter I (or lowercase letter L) for the digit one, and the uppercase O for the zero.[7]

The 0 key was added and standardized in its modern position early in the history of the typewriter, but the 1 and exclamation point were left off some typewriter keyboards into the 1970s.[8]

Combined characters

In early designs, some characters were produced by printing two symbols with the carriage in the same position. For instance, the exclamation point, which shares a key with the numeral 1 on post-mechanical keyboards, could be reproduced by using a three-stroke combination of an apostrophe, a backspace, and a period. A semicolon (;) was produced by printing a comma (,) over a colon (:). As the backspace key is slow in simple mechanical typewriters (the carriage was heavy and optimized to move in the opposite direction), a more professional approach was to block the carriage by pressing and holding the space bar while printing all characters that needed to be in a shared position. To make this possible, the carriage was designed to advance only after releasing the space bar.

In the era of mechanical typewriters, combined characters such as é and õ were created by the use of dead keys for the diacritics (′, ~), which did not move the paper forward. Thus the ′ and e would be printed at the same location on the paper, creating é.

Contemporaneous alternatives

There were no particular technological requirements for the QWERTY layout,[2] since at the time there were ways to make a typewriter without the "up-stroke" typebar mechanism that had required it to be devised. Not only were there rival machines with "down-stroke" and "front stroke" positions that gave a visible printing point, the problem of typebar clashes could be circumvented completely: examples include Thomas Edison's 1872 electric print-wheel device which later became the basis for Teletype machines; Lucien Stephen Crandall's typewriter (the second to come onto the American market in 1883) whose type was arranged on a cylindrical sleeve; the Hammond typewriter of 1885 which used a semi-circular "type-shuttle" of hardened rubber (later light metal); and the Blickensderfer typewriter of 1893 which used a type wheel. The early Blickensderfer's "Ideal" keyboard was also non-QWERTY, instead having the sequence "DHIATENSOR" in the home row, these 10 letters being capable of composing 70% of the words in the English language.[9]

Properties

Alternating hands while typing is a desirable trait in a keyboard design. While one hand types a letter, the other hand can prepare to type the next letter, making the process faster and more efficient. In the QWERTY layout many more words can be spelled using only the left hand than the right hand. Thousands of English words can be spelled using only the left hand, while only a couple of hundred words can be typed using only the right hand[10] (the three most frequent letters in the English language, ETA, are all typed with the left hand). In addition, more typing strokes are done with the left hand in the QWERTY layout. This is helpful for left-handed people but disadvantageous for right-handed people.

Contrary to popular belief, the QWERTY layout was not designed to slow the typist down,[2]: 162 but rather to speed up typing. Indeed, there is evidence that, aside from the issue of jamming, placing often-used keys farther apart increases typing speed, because it encourages alternation between the hands.[11] (On the other hand, in the German keyboard the Z has been moved between the T and the U to help type the frequent digraphs TZ and ZU in that language.) Almost every word in the English language contains at least one vowel letter, but on the QWERTY keyboard only the vowel letter A is on the home row, which requires the typist's fingers to leave the home row for most words.

A feature much less commented on than the order of the keys is that the keys do not form a rectangular grid, but rather each column slants diagonally. This is because of the mechanical linkages – each key is attached to a lever, and hence the offset prevents the levers from running into each other – and has been retained in most electronic keyboards. Some keyboards, such as the Kinesis or TypeMatrix, retain the QWERTY layout but arrange the keys in vertical columns, to reduce unnecessary lateral finger motion.[12][13]

Computer keyboards

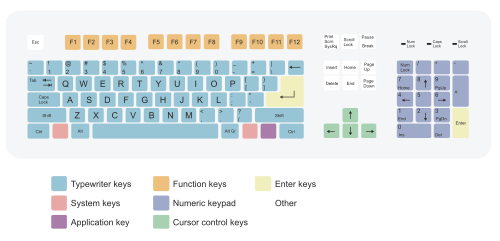

The first computer terminals such as the Teletype were typewriters that could produce and be controlled by various computer codes. These used the QWERTY layouts and added keys such as escape Esc which had special meanings to computers. Later keyboards added function keys and arrow keys. Since the standardization of personal computers and Windows after the 1980s, most full-sized computer keyboards have followed this standard (see drawing at right). This layout has a separate numeric keypad for data entry at the right, 12 function keys across the top, and a cursor section to the right and center with keys for Insert, Delete, Home, End, Page Up, and Page Down with cursor arrows in an inverted-T shape.[14]

Diacritical marks

QWERTY was designed for English, a language with accents ('diacritics') appearing only in a few words of foreign origin. The standard US keyboard has no provision for these at all; the need was later met by the so-called "US-International" keyboard mapping, which uses "dead keys" to type accents without having to add more physical keys. (The same principle is used in the standard US keyboard layout for macOS, but in a different way). Most European (including UK) keyboards for PCs have an AltGr key ('Alternative Graphics' key,[a] replaces the right Alt key) that enables easy access to the most common diacritics used in the territory where sold. For example, default keyboard mapping for the UK/Ireland keyboard has the diacritics used in Irish but these are rarely printed on the keys; but to type the accents used in Welsh and Scots Gaelic requires the use of a "UK Extended" keyboard mapping and the dead key or compose key method. This arrangement applies to Windows, ChromeOS and Linux; macOS computers have different techniques. The US International and UK Extended mappings provide many of the diacritics needed for students of other European languages.

Other keys and characters

Some QWERTY keyboards have alt codes, in which holding Alt while inputting a sequence of numbers on a numeric keypad allows the entry of special characters. For example, Alt+163 results in ú (a Latin lowercase letter u with an acute accent).

Specific language variants

There are a large number of QWERTY keyboard layouts used for languages written in the Latin script, the most popular layouts include English, Czech, Danish, Dutch, Estonian, Faroese, Icelandic, Irish, Italian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Maltese, Norwegian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Turkish, Vietnamese languages.

Minor changes to the arrangement are made for other languages. There are a large number of different keyboard layouts used for different languages written in Latin script. They can be divided into three main families according to where the Q, A, Z, M, and Y keys are placed on the keyboard. These are usually named after the first six letters, for example this QWERTY layout and the AZERTY layout.

Multilingual variants

Multilingual keyboard layouts, unlike the default layouts supplied for one language and market, try to make it possible for the user to type in any of several languages using the same number of keys. Mostly this is done by adding a further virtual layer in addition to the ⇧ Shift-key by means of AltGr (or 'right Alt' reused as such), which contains a further repertoire of symbols and diacritics used by the desired languages.

This section also tries to arrange the layouts in ascending order by the number of possible languages and not chronologically according to the Latin alphabet as usual.

United Kingdom (Extended) Layout

Windows

From Windows XP SP2 onwards, Microsoft has included a variant of the British QWERTY keyboard (the "United Kingdom Extended" keyboard layout) that can additionally generate several diacritical marks. This supports input on a standard physical UK keyboard for many languages without changing positions of frequently used keys, which is useful when working with text in Welsh, Scots Gaelic and Irish — languages native to parts of the UK (Wales, parts of Scotland and Northern Ireland respectively).

In this layout, the grave accent key (`¦) becomes, as it also does in the US International layout, a dead key modifying the character generated by the next key pressed. The apostrophe, double-quote, tilde and circumflex (caret) keys are not changed, becoming dead keys only when 'shifted' with AltGr. Additional precomposed characters are also obtained by shifting the 'normal' key using the AltGr key. The extended keyboard is software installed from the Windows control panel, and the extended characters are not normally engraved on keyboards.

The UK Extended keyboard uses mostly the AltGr key to add diacritics to the letters a, e, i, n, o, u, w and y (the last two being used in Welsh) as appropriate for each character, as well as to their capitals. Pressing the key and then a character that does not take the specific diacritic produces the behaviour of a standard keyboard. The key presses followed by spacebar generate a stand-alone mark.:

- grave accents (e.g. à, è, etc.) needed for Scots Gaelic are generated by pressing the grave accent (or 'backtick') key `, which is a dead key, then the letter. Thus `+a produces à.

- acute accents (e.g. á) needed for Irish are generated by pressing the AltGr key together with the letter.[b] Thus AltGr+a produces á; AltGr+⇧ Shift+a produces Á.

- the circumflex diacritic needed for Welsh may be added by AltGr+6, acting as a dead key combination, followed by the letter. Thus AltGr+6 then a produces â, AltGr+6 then w produces the letter ŵ.

Some other languages commonly studied in the UK and Ireland are also supported to some extent:

- diaeresis or umlaut (e.g. ä, ë, ö, etc.) is generated by a dead key combination AltGr+2, then the letter. Thus AltGr+2a produces ä.

- tilde (e.g. ã, ñ, õ, etc., as used in Spanish and Portuguese) is generated by dead key combination AltGr+#, then the letter. Thus AltGr+#a produces ã.

- cedilla (e.g. ç) under c is generated by AltGr+C, and the capital letter (Ç) is produced by AltGr+⇧ Shift+C

The AltGr and letter method used for acutes and cedillas does not work for applications which assign shortcut menu functions to these key combinations.

These combinations are intended to be mnemonic and designed to be easy to remember: the circumflex accent (e.g. â) is similar to the free-standing circumflex (caret) (^), printed above the 6 key; the diaeresis/umlaut (e.g. ö) is visually similar to the double-quote (") above 2 on the UK keyboard; the tilde (~) is printed on the same key as the #.

The UK Extended layout is almost entirely transparent to users familiar with the UK layout. A machine with the extended layout behaves exactly as with the standard UK, except for the rarely used grave accent key. This makes this layout suitable for a machine for shared or public use by a user population in which some use the extended functions.

Despite being created for multilingual users, UK-Extended in Windows does have some gaps — there are many languages that it cannot cope with, including Romanian and Turkish, and all languages with different character sets, such as Greek and Russian. It also does not cater for thorn (þ, Þ) in Old English, the ß in German, the œ in French, nor for the å, æ, ø, ð, þ in Nordic languages.

ChromeOS

The UK default layout ("GB") in Chrome OS provides all the same combinations as with Windows, but adds many more symbols and dead keys via AltGr.

| ¬ ¦ ` ◌ |

! ¡ 1 ¹ |

" ½ 2 ◌ |

£ ⅓ 3 ⅓ |

$ ¼ 4 € |

% ⅜ 5 ½ |

^ ⅝ 6 ◌ |

& ⅞ 7 { |

* ™ 8 [ |

( ± 9 ] |

) ° 0 } |

_ ¿ - \ |

+ ◌ = ◌ |

| tab | Q Ω q @ |

W Ẃ w ẃ |

E É e é |

R ® r ¶ |

T Ŧ t ŧ |

Y Ý y ý |

U Ú u ú |

I Í i í |

O Ó o ó |

P Þ p þ |

{ ◌ [ ◌ |

} ◌ ] ◌ |

| 🔍 | A Á a á |

S § s ß |

D Ð d ð |

F ª f đ |

G Ŋ g ŋ |

H Ħ h ħ |

J ◌ j ◌ |

K & k ĸ |

L Ł l ł |

: ◌ ; ◌ |

@ ◌ ' ◌ |

~ ◌ # ◌ |

| shift | | ¦ \ | |

Z < z « |

X > x » |

C Ç c ç |

V ‘ v “ |

B ’ b ” |

N N n n |

M º m µ |

< × , ─ |

> ÷ . · |

? ◌ / ◌ |

shift |

Notes:

- Dotted circle (◌) is used here to indicate a dead key.

- AltGr+⇧ Shift+0 (°) is a degree sign; AltGr+⇧ Shift+M (º) is a masculine ordinal indicator

- As of March 2025[update], the combinations AltGr+⇧ Shift+2 and AltGr+5 both produce a 1⁄2 symbol: there is no key for ² (U+00B2 ² SUPERSCRIPT TWO, "squared sign").

- The diacritics used in the United Kingdom's native languages (English, Welsh, Scottish Gaelic and Irish[c] ) are provided by using deadkey combinations below.

Dead keys

- AltGr+`+letter produces grave accents (e.g., à/À).

- AltGr+2(release)letter produces diaeresis accents (e.g., ä/Ä)

- AltGr+6(release)letter produces circumflex accents (e.g., â/Â)

- AltGr+= (release) letter produces (mainly) comma diacritic or cedilla below the letter e.g., ş/Ş

- AltGr+⇧ Shift+= (release) letter produces a hook (diacritic) on vowels (e.g., ą/Ą)

- AltGr+[ same as AltGr+2

- AltGr+] same as AltGr+#

- AltGr+{(release)letter produces overrings (e.g., å/Å)

- AltGr+}(release)letter produces macrons (e.g., ā/Ā)

- AltGr+j(release)letter produces mainly horn (diacritic)s (e.g., ả/Ả)

- AltGr+⇧ Shift+j(release)letter is a dead key that appears to have no function (as of March 2025[update])

- AltGr+;(release)letter produces acute accents (e.g., ź/Ź)

- AltGr+⇧ Shift+;(release)letter is another dead key that appears to have no function

- AltGr+'(release)letter produces acute accents (e.g., á/Á)

- AltGr+⇧ Shift+'(release)letter produces caron (haček) diacritics (e.g., ǎ/Ǎ)

- AltGr+#(release)letter produces tilde diacritics (e.g., ã/Ã)

- AltGr+⇧ Shift+#(release)letter produces inverted breve diacritics (e.g., ă/Ă)

- AltGr+/(release)letter produces mainly underdots (e.g., ạ/Ạ)

- AltGr+⇧ Shift+/(release)letter produces mainly overdots (e.g., ȧ/Ȧ)

Finally, any arbitrary Unicode glyph can be produced given its hexadecimal code point: ctrl+⇧ Shift+u, release, then the hex value, then space bar or ↩ Return. For example ctrl+⇧ Shift+u (release) 1234space produces the Ethiopic syllable SEE, ሴ. ̣̣̣̣

US-International

Windows provides an alternative layout for a US keyboard to type diacritics, called the US-International layout. Linux and ChromeOS (which calls it the International/Extended keyboard[citation needed]) also provide this layout with slight modifications such as many more AltGr combinations.

The layout is installed from the settings panel.[15] The additional functions (shown in blue) may or may not be engraved on the keyboard, but are always functional. It can be used to type most major languages from Western Europe: Afrikaans, Danish, Dutch, English, Faroese, Finnish, German, Icelandic, Irish, Italian, Norwegian, Portuguese, Scots Gaelic, Spanish, and Swedish. It is not sufficient for French because it lacks the grapheme “œ/Œ” (as does every keyboard layout provided by Windows except the Canadian multilingual standard keyboard). Some less common western and central European languages (such as Welsh, Maltese, Czech and Hungarian), are not fully supported. If the keyboard does not have an AltGr key, the right-hand Alt is used. If that key does not exist (which is true of many laptops) the combination Ctrl+Alt works as well.

This layout uses keys ', `, ", ^ and ~ as dead keys to generate characters with diacritics by pressing the appropriate key, then the letter on the keyboard. Only certain letters such as vowels and "n", work, otherwise the symbol is produced followed by the typed letter. To get only the symbol ', `, ", ^ and ~, press the Spacebar after the key.

- ' + vowel → vowel with acute accent, e.g., '+e → é

- ` + vowel → vowel with grave accent, e.g., `+e → è

- " + vowel → vowel with diaeresis (or umlaut), e.g., "+e → ë

- ^ + vowel → vowel with circumflex accent, e.g., ^+e → ê

- ~ + a, n or o → letter with tilde, e.g. ~+n → ñ, ~+o → õ

- ' + c → ç (Windows) or ć (X11)

The layout is not entirely transparent to users familiar with the conventional US layout as the dead keys act different (they don't appear immediately and produce accented letters depending on what letter is typed next). This could be disconcerting on a machine for shared or public use. There are alternatives, such as requiring AltGr to be held down to get the dead-key function.

US-International in the Netherlands

The Dutch layout is historical, and keyboards with this layout are rarely used. Instead, the standard keyboard layout in the Netherlands is US-International, as the Dutch language heavily relies on diacritics and the US-International keyboard provides easy access to diacritics using dead keys. While many US keyboards do not have AltGr or extra US-International characters engraved on them, Dutch keyboards typically have the AltGr engraved at the location of the right Alt key, and have the euro sign € engraved next to the 5 key.

Apple International English Keyboard

There are three kinds of Apple Keyboards for English: the United States, the United Kingdom and International English. The International English version features the same changes as the United Kingdom version, only without substituting # for the £ symbol on ⇧ Shift+3, and as well lacking visual indication for the € symbol on ⌥ Option+2 (although this shortcut is present with all Apple QWERTY layouts).

Differences from the US layout are:

- The ~

` key is located on the left of the Z key, and the |

\ key is located on the right of the "

' key. - The ±

§ key is added on the left of the !

1 key. - The left ⇧ Shift key is shortened and the Return key has the shape of inverted L.

Canadian Multilingual Standard

The Canadian Multilingual Standard keyboard layout is used by some Canadians. Though the caret (^) is missing, it is easily inserted by typing the circumflex accent followed by a space.

Finnish multilingual

The visual layout used in Finland is basically the same as the Swedish layout. This is practical, as Finnish and Swedish share the special characters Ä/ä and Ö/ö, and while the Swedish Å/å is unnecessary for writing Finnish, it is needed by Swedish-speaking Finns and to write Swedish family names which are common.

As of 2008, there is a new standard for the Finnish multilingual keyboard layout, developed as part of a localization project by CSC. All the engravings of the traditional Finnish–Swedish visual layout have been retained, so there is no need to change the hardware, but the functionality has been extended considerably, as additional characters (e.g., Æ/æ, Ə/ə, Ʒ/ʒ) are available through the AltGr key, as well as dead keys, which allow typing a wide variety of letters with diacritics (e.g., Ç/ç, Ǥ/ǥ, Ǯ/ǯ).[16][17]

Based on the Latin letter repertory included in the Multilingual European Subset No. 2 (MES-2) of the Unicode standard, the layout has three main objectives. First, it provides for easy entering of text in both Finnish and Swedish, the two official languages of Finland, using the familiar keyboard layout but adding some advanced punctuation options, such as dashes, typographical quotation marks, and the non-breaking space (NBSP).

Second, it is designed to offer an indirect but intuitive way to enter the special letters and diacritics needed by the other three Nordic national languages (Danish, Norwegian and Icelandic) as well as the regional and minority languages (Northern Sámi, Southern Sámi, Lule Sámi, Inari Sámi, Skolt Sámi, Romani language as spoken in Finland, Faroese, Kalaallisut also known as Greenlandic, and German).

As a third objective, it allows for relatively easy entering of particularly names (of persons, places or products) in a variety of European languages using a more or less extended Latin alphabet, such as the official languages of the European Union (excluding Bulgarian and Greek). Some letters, like Ł/ł needed for Slavic languages, are accessed by a special "overstrike" key combination acting like a dead key.[18] Initially the Romanian letters Ș/ș and Ț/ț (S/s and T/t with comma below) were not supported (the presumption was that Ş/ş and Ţ/ţ (with cedilla) would suffice as surrogates), however the layout was updated in 2019 to include the letters with the commas as well.[19]

EurKEY

EurKEY, a multilingual keyboard layout intended for Europeans, programmers and translators which uses the US-standard QWERTY layout as base and adds a third and fourth layer available through the AltGr key and AltGr+⇧ Shift. These additional layers provide support for many Western European languages, special characters, the Greek alphabet (via dead keys), and many common mathematical symbols.

Unlike most of the other QWERTY layouts, which are formal standards for a country or region, EurKEY is not an EU, EFTA or any national standard.

To address the ergonomics issue of QWERTY, EurKEY Colemak-DH was also developed a Colmak-DH version with the EurKEY design principles.

Alternatives

Several alternatives to QWERTY have been developed over the years, claimed by their designers and users to be more efficient, intuitive, and ergonomic. Nevertheless, none have seen widespread adoption, partly due to the sheer dominance of available keyboards and training.[20] Although some studies have suggested that some of these may allow for faster typing speeds,[21] many other studies have failed to do so, and many of the studies claiming improved typing speeds were severely methodologically flawed or deliberately biased, such as the studies administered by August Dvorak himself before and after World War II.[citation needed] Economists Stan Liebowitz and Stephen Margolis have noted that rigorous studies are inconclusive as to whether they actually offer any real benefits,[22] and some studies on keyboard layout have suggested that, for a skilled typist, layout is largely irrelevant – even randomized and alphabetical keyboards allow for similar typing speeds to QWERTY and Dvorak keyboards – and that switching costs always outweigh the benefits of further training with a keyboard layout a person has already learned.[citation needed]

The most widely used such alternative is the Dvorak keyboard layout; another alternative is Colemak, which is based partly on QWERTY and is claimed to be easier for an existing QWERTY typist to learn while offering several supposed optimisations.[23] Most modern computer operating systems support these and other alternative mappings with appropriate special mode settings, with some modern operating systems allowing the user to map their keyboard in any way they like, but few keyboards are made with keys labeled according to any other standard.

Comparison to other keyboard input systems

Comparisons have been made between Dvorak, Colemak, QWERTY, and other keyboard input systems, namely stenotype or its electronic implementations. However, stenotype is a fundamentally different system, which relies on phonetics and simultaneous key presses or chords. Although Shorthand (or 'stenography') has long been known as a faster and more accurate typing system,[citation needed] adoption has been limited, possibly due to the historically high cost of equipment, steeper initial learning curve, and low awareness of the benefits within primary education and in the general public.[citation needed]

The first typed shorthand machines appeared around 1830, with English versions gaining popularity in the early 1900s.[citation needed] Modern electronic stenotype machines or programs produce output in written language,[citation needed] which provides an experience similar to other keyboard setups that immediately produce legible work.

Half QWERTY

A half QWERTY keyboard is a combination of an alpha-numeric keypad and a QWERTY keypad, designed for mobile phones.[24] In a half QWERTY keyboard, two characters share the same key, which reduces the number of keys and increases the surface area of each key, useful for mobile phones that have little space for keys.[24] It means that 'Q' and 'W' share the same key and the user must press the key once to type 'Q' and twice to type 'W'.

See also

- HCESAR

- JCUKEN

- Colemak Keyboard

- Dvorak keyboard layout

- KALQ keyboard split-screen touchscreen thumb-typing Android-only 2013 beta

- Keyboard monument

- Maltron keyboard

- Path dependence

- Repetitive strain injury

- Text entry interface

- Thumb keyboard

- Touch typing

- Velotype

- Virtual keyboard

- WASD

Notes

- ^ Where this key is not provided, some layouts provide its equivalent using ctrl+alt+the letter to be accented, which can mean some chords that require additional manual dexterity.

- ^ The sequence AltGr+' – acting as a dead key combination – followed by the letter, has the same effect. This inconvenient facility is rarely used, being needed only for use with programs that use the combination of AltGr and a letter (or Ctrl+Alt and letter) for other functions, in which case the AltGr+' method must be used to generate acute accents.

- ^ The acute accent in Irish is additionally provided using AltGr+vowel.

References

- ^ a b US 79868, Shole, C. Latham; Glidden, Carlos & Soule, Samuel W., "Improvement in Type-writing Machines", issued 14 July 1868

- ^ a b c d e f g Yasuoka, Koichi; Yasuoka, Motoko (March 2011). "On the Prehistory of QWERTY" (PDF). ZINBUN. 42: 161–174. doi:10.14989/139379. S2CID 53616602. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 September 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ a b Yasuoka, Koichi; Yasuoka, Motoko (2008). Myth of QWERTY Keyboard. Tokyo: NTT Publishing. ISBN 9784757141766. Archived from the original on 9 March 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ^ David, Paul A. (1985), "Clio and the Economics of QWERTY", American Economic Review, 75 (2), American Economic Association: 332–337, JSTOR 1805621

- ^ David, P. A. (1986). "Understanding the Economics of QWERTY: the Necessity of History". In Parker, William N., Economic History and the Modern Economist. Basil Blackwell, New York and Oxford.

- ^ US 207559, Sholes, Christopher Latham, issued 27 August 1878

- ^ Weller, Charles Edward (1918), The early history of the typewriter, La Porte, Indiana: Chase & Shepard, printers, hdl:2027/nyp.33433006345817

- ^ See for example the Olivetti Lettera 36 Archived 27 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, introduced in 1972

- ^ Shermer, Michael (2008). The mind of the market. Macmillan. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8050-7832-9.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (April 1997), "The Curse of QWERTY", Discover, archived from the original on 20 September 2008, retrieved 29 April 2009,

More than 3,000 English words utilize QWERTY's left hand alone, and about 300 the right hand alone.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (30 October 1981). "Was the QWERTY keyboard purposely designed to slow typists?". straightdope.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Kinesis – Ergonomic Benefits of the Contoured Keyboard Archived 28 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine – Vertical key layout

- ^ TypeMatrix. "TypeMatrix - The Keyboard is the Key". typematrix.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Castillo, M. (2 September 2010). "QWERTY, @, &, #". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 32 (4): 613–614. doi:10.3174/ajnr.a2228. ISSN 0195-6108. PMC 7965893. PMID 20813871.

- ^ How to use the United States-International keyboard layout in Windows 7, in Windows Vista, and in Windows XP Archived 4 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Microsoft, 17 August 2009

- ^ SFS 5966 (keyboard layout), Finnish Standards Association SFS, 3 November 2008, archived from the original on 5 December 2014, retrieved 19 April 2015. Finnish-Swedish multilingual keyboard setting.

- ^ Kotoistus (12 December 2006), Uusi näppäinasettelu [Status of the new Keyboard Layout] (in Finnish and English), CSC IT Center for Science, archived from the original (presentation page collecting drafts of the Finnish Multilingual Keyboard) on 27 April 2015, retrieved 19 April 2015

- ^ "Precomposed characters in the new Finnish keyboard layout specification" (PDF). Kotoistus. 29 June 2006. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Korpela, Jukka. "Suomalainen monikielinen näppäimistö" [Finnish multilingual keyboard] (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Gould, Stephen Jay (1987) "The Panda's Thumb of Technology." Natural History 96 (1): 14-23; Reprinted in Bully for Brontosaurus. New York: W.W. Norton. 1992, pp. 59-75.

- ^ Paul David, "Understanding the economics of QWERTY: the necessity of history", Economic history and the modern economist, 1986

- ^ Liebowitz, Stan; Margolis, Stephen E. (1990), "The Fable of the Keys", Journal of Law and Economics, 33 (1): 1–26, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.167.110, doi:10.1086/467198, S2CID 14262869

- ^ Krzywinski, Martin. "Colemak – Popular Alternative". Carpalx – keyboard layout optimizer. Canada's Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Half-QWERTY keyboard layout – Mobile terms glossary". GSMArena.com. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2011.